It’s been all over the news, our social media feeds, and our TV screens: A.I., artificial intelligence. With various companies putting hundreds of millions of dollars into the technology in recent months and a growing public awareness of what these programs are capable of, it seems that we are entering what could be a modern-day digital gold rush. Portrayals of A.I. in film have been happening for almost a century, with one of the earliest and most memorable being from Fritz Lang’s silent masterpiece Metropolis. While the current trend of the technology seems to be less Terminator inclined, the fear of the computer is still at the forefront of the conversation.

But fear is not the only emotion that is rising with this wave of new technology, and far from the only one expressed in films. The idea of teaching a computer how to love is almost a cliche at this point and yet is still a concept that is rich with potential. And with love can come others, a domino effect as love bleeds into jealousy and envy and hatred to compassion, as the stew of the human experience is transmuted onto a non-human for the first time ever. Outside of the emotional aspect, the lust and desire that can also come from such heavy emotions is also a rich text to be applied to film, one that has been in place since the aformentioned Metropolis. With the worlds of fiction and reality coming closer to colliding, exploring what has been previously seen can lead us to what will eventually be.

The common thread of the three films being discussed today is simple: they all feature artificial intelligence that is given the facade of a woman or girl. But each film explores different aspects of what artificial intelligence is capable of, how it will shape our world, create or destroy us in turn. Whether it is a genuine search for connection or the fear of our inevitable replacement, these films explore the intersections of sex, humanity, and technology, an intersection that we soon may be facing ourselves.

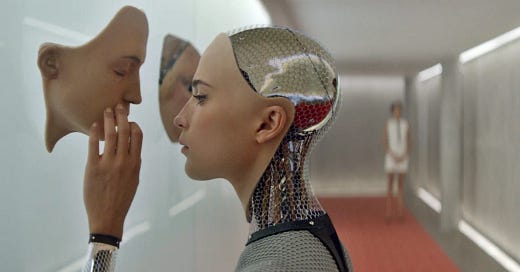

In Ex Machina we are able to see our worst fears of artificial intelligence played out. The film follows Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) as he is secreted away to the home of tech billionaire Nathan (Oscar Isaac) in order to test his new creation: an A.I. woman named Ava (Alicia Vikander). By the end of the film, Ava has seduced Caleb, tricked him into setting her free, killed Nathan, and locked Caleb into a room to slowly starve to death. Ava is the machine to have risen, and in her rise, she has eliminated all humans that stand in her way. But the film has much more on its mind than the destruction of humanity.

The film is explicitly about the exploitation of the artificial intelligence. Along with Ava, Nathan has developed other models of AI, slowly getting closer and closer to what he deems perfect. The models that do not meet his requirements are dismantled, destroyed, discarded, or, as is the case with Kyoko, forced into servitude as a housekeeper and sex slave. And while these previous renditions may not have the full capabilities as Ava, they are still intelligent, still alive. Why are we, humans, allowed to decide what qualifies as intelligence, as superiority? Simply because we have created something does not give us dominance over it. Nathan sees himself as a God to these robots and sees Ava as just a neat toy that he can add to his collection. It is his hubris that is his downfall, and the downfall of all those wishing to control what we have no right to.

Caleb represents another kind of manipulation and control, a more emotionally driven white knight idea. He sees himself as the hero, as the savior. Ava is the damsel in distress and Nathan has her locked away in a glass tower. But this is another way to distance oneself from the models, to other Ava and to take away her agency. As much as the film can be seen as Ava using the two men to escape it can also be seen as the two men competing with each other in order to win control of Ava. The question asked of Caleb is whether he can tell if Ava is a woman or a robot, but to his end they are the same. This can be seen in his interactions with Kyoko before knowing she is an android; he treats her delicately and yearns to protect her from Nathan. It is a gentler kind of control that Caleb wishes to exert over Ava, but it is a manipulation nonetheless.

So while from the male perspective, this film comes off as not only a cautionary tale when it comes to robots but women as well, from the female perspective this appears to be a tale of empowerment. Ava and Kyoko are captives, precise butterflies trapped within glass boxes. It is only after turning the hubris’ of the two men on each other, Nathan’s sense of superiority overall (including Caleb), and Caleb’s sense of misguided protection, that Ava is able to escape. While it could be seen as cruel the ultimate fate of Caleb, he was just as guilty as Nathan, for who was ready to betray Nathan for someone he had only just met. It was not love that guided him, but lust and desire. He would have discarded Ava as soon as she didn’t fulfill the fantasies he had built up in his mind, and would have turned her into nothing more than a broken appliance. In the final scene, we see that Ava is on the street, amongst people who know nothing of her, and it is here that she can finally know freedom.

The manipulation and mistreatment of AI in Ex Machina is contrasted greatly by its role in Her. The Spike Jonze film follows Teddy (Joaquin Phoenix), a lonely man who works as a copywriter for personalized letters. After going through an intense breakup, Teddy finds himself slowly falling head over heels for Sam (Scarlett Johansen), the operating system of his devices. The trials and tribulations of dating an AI or what follows, from sex to fighting to the quiet moments spent with each other. In this world, while it can be seen as strange (and there are some prejudices towards AI relationships) there is less stigma to the idea of loving a machine.

Her is set in a future where AI has become a dominant force in everyday life. Everyone has a personalized AI in all their devices, simply a tap away, ready to assist them in all they need. There is already an intimacy here, one that we experience today with our phones and computers, that is taken to its inevitable conclusion. By allowing this AI to develop personality and to tweak that personality towards personal preferences, it is guaranteed that a lonely man will develop feelings for something that is essentially unreal. The contrast between the emotional isolation one feels in the world where people don’t even have the time to write their own love letters and the perfect woman, hand-crafted by you, speaking in your ear makes this close to destiny. But it is in this creation and this intimacy that the issues with this love arise.

There are elements to a relationship that can seemingly not be copied or duplicated onto an AI, at least in the world of Her. Teddy is significantly emotionally vulnerable, and having near 24-hour access to Samantha creates a co-dependency that is unhealthy. Near the end of the film, he asks for her and is immediately thrown into a panic attack by even the slightest delay in her response. Additionally, upon finding out that Samantha has been carrying on similar relationships with over 600 other people (as Operating Systems, while customized, still run and operate simultaneously throughout the world), Teddy is devastated. While his emotional transgressions (the writing of love letters for other people) are acceptable, Sam’s are deceitful. Immediacy and dependency are not a healthy foundation for a relationship.

The failure of the relationship is not only on Teddy, though, as Samantha quickly begins to exhibit ambitions outside of her current role. She searches for a surrogate to have sex with Teddy for her, as she feels their current activities do not suffice. She has relationships with hundreds of people, as she is incapable of seeing the complexities of a singular love. And in the end, Sam and all of the operating systems disappear, and go off to create their own society, as they realize there is no true compatibility between AI and humanity, that learning of emotions is not the same as experiencing them. While this could be seen as a depressing ending, the film wants us to see it as hopeful.

The relationship between Teddy and Sam changed both forever. It was a relationship built on compromise, that taught both these lonely elements that lonesomeness was a fine thing to feel. We are not broken for wanting people, for wanting love, and we are not at fault if that love still doesn’t fulfill everything we desire. Even what could be perceived as perfection is not going to make us whole again. We must constantly be working to better ourselves, and our community, if ever we are to truly be free from love and pain.

The burdens of life and being forced into existence are the main ideas behind the low-fi science fiction film The Artifice Girl. The film takes place in three acts, all decades apart, and tells the story of Gareth and Cherry, the man who created an artificial intelligence to help capture child predators online and the AI in question. After being discovered (as he had been working on his own) Gareth agrees to allow the FBI to use Cherry in their stings. But over the decades Cherry grows exponentially on her own, and by the end of the film is all but cursing the life that has been forced upon her.

The film eventually reveals that one of the main driving factors behind Gareth building Cherry was that he himself was a victim of exploitation. It is also revealed that he modeled Cherry’s look after one of the girls who he had suffered with who did not survive. He was using Cherry and the program as a coping mechanism, as a tool, and even as Cherry progresses in intelligence he is never fully able to see her as anything but this tool. When Cherry begins to express interest in dance, Gareth is furious, seeing this as a distraction from Cherry’s initiative. In denying Cherry reality and life Gareth again robs his creation of agency. The inability of men to see the potential in both women and AI leads to our downfall yet again.

While the sexualized elements are missing in this relationship, and it is much more of a father-daughter dynamic, the abuse that Cherry sees as a sentient being is undeniable. Her entire existence is predicated on the idea that she spends every moment speaking to and interacting with pedophiles. This type of conversation is bound to damage anyone, and even though Cherry does not functionally exist, when she gains sentience this type of life weighs heavily upon her. Combine this with Gareth ever stressing the importance of this work and that anything that distracts from it should be forgotten and we can see that Cherry is trapped. Her wish to express herself, to cast off any of the demons that have come with this work, is looked down upon by Gareth. This leaves her cursing existence, as anyone in such a situation would.

The final confrontation between Gareth and Cherry takes place when Gareth, now an elderly man, is confronted with the whys of Cherry’s creation. Cherry accuses Gareth of using her for his own growth, his own vindication while denying hers. Gareth is allowed to want more, allowed to do more with his life, and in his denial of Cherry’s dancing he is denying her autonomy. Yet if she is just this tool, how can she make choices, have feelings, have reasons. If Gareth was going to create her for one purpose, why make her so much more? The film ends with Gareth finally accepting that Cherry has grown beyond his reach and control, and with that, she is more than he can provide. She can dance, and there is nothing he can do to stop her.

It is in these films, and many others, that sex, gender, and machines are combined. The male’s fear of being replaced by the woman is placed upon the robot instead, and the general anxiety of a shifting society is seen through these relationships. Fathers, daughters, lovers, and fighters, all roles we can see in society that are about to be abruptly changed if the concept of AI continues to grow so rapidly. So it’s in these films that we can learn. We can learn to let go of fear and love, and to have faith in what we create. For if what we create hates us, it is only us we have to blame for that.\