Lucky Star

Director Gillian McKercher

85 mins

I am always cautious when approaching a Canadian film at a festival. There tends to be a sheen to our homegrown cinema, a quaintness that is hard for our creative forces to overcome. Whether it’s from a storytelling angle, with our films lacking in depth of character, or smaller things that indicate a production that didn’t quite have the time, money, or talent to make the film a complete vision. I am more than happy to report that, while not lacking this veneer entirely, Lucky Star doesn’t fall into the trappings of many a independent Canadian production would. Following Lucky, a middle aged former gambling addict as he desperately tries to get enough money to keep his life from falling apart, the film plays out like a Canadian Uncut Gems. While that film used the unending frenzy of New York City to create a frenetic tableau of a man, Lucky Star uses the cold and disinterested streets of Calgary to highlight the emotional isolation Lucky places himself in.

The film succeeds because of the character of Lucky and because of the fantastic performance by Terry Chen. Chen makes Lucky a lovable loser, a man who can’t help but make the wrong choice at almost every opportunity. Despite consistently digging his own grave we root for Lucky, we want him to succeed and want him to keep his family together. Writer-director Gillian McKercher gives the film a proper amount of humor and light-heartedness, while undercutting this with a genuine sense of danger. Every time Lucky takes another chance, makes another gamble (whether literally or figuratively) we know this could spell complete disaster. McKercher walks a fine line between having the film be treacly and having it be harsh.

There are still elements of the film that fail due to either one element or another, and that leave it with that Canadian indie veneer. Odd line readings, somewhat uninspired camerawork, and a relative lack of stakes compared to it’s American counterpart do hold the film back from outright greatness. One can not help but wonder if they had the money for more takes, if they could have cast a wider net for bit part actors, if they had simply a few more dollars to invest in staging their scenes better at times, what the film really could have come to. One thing that plagues Canadian film is a flatness in the image, a lack of style in our lighting. Our dramas come across as drab and one note in their lighting design, like television movies or soap operas, and this lack of creativity in the cinematography does make some of the family scenes dull to watch.

In the end this is a very well done indie drama, with great lead performances and a script that allows for a dramatic growth in the characters. The film excels in it’s use of unstated backstory. We watch our characters interact with each other and know exactly what kind of people they are and the relationships they have with each other. McKercher’s camera focuses heavily on the (real) tattoos of Terry Chen, adding layers of backstory to Lucky without a word being spoken. It’s this element of effortless storytelling that makes me excited for McKercher’s future films, and Chen’s future performances.

The End

Director Joshua Oppenheimer

148 mins

This was one of my most anticipated screenings of the festival, and not without warrant. Acclaimed documentary director Joshua Oppenheimer, who stunned audiences with his explorations of the Cambodian genocide in both The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence, takes his first swing at a narrative feature. And what a swing it is, writing and directing an original post-apocalyptic musical. Following a small group of survivors in their bunker over twenty years after the outside world has all but collapsed, we follow the son (George MacKay), who was born in the bunker and has been raised sheltered and fearful. He’s raised by his father (Michael Shannon), a man who made millions on fossil fuels and energies that helped destroy the world, and his mother (Tilda Swinton), a former ballerina. The family, along with their small support staff, believe themselves to be the only humans left alive until one day they are proven wrong.

The highlight of the film is it’s cast, with McKay, Swinton, and Shannon all turning in great performances. Shannon is a standout as the blustering billionaire, at times hilariously aloof and unaware, at others painfully wielding his power over the occupants of the bunker. Swinton plays the over-protective and neurotic mother well, and as the themes of abandonment and sacrifice are brought forth later in the film, she has many powerful beats to play. MacKay’s path from wide-eyed youth to grown man is, while somewhat obvious, still played with gumption and sublime resonance by the actor. Unfortunately, their performances are great despite of the script and direction, not because of it.

As much as I wished this film would be the best of the festival, it was an undeniable slog. The songs felt incredibly one-beat and unmemorable, each just a droning, uninteresting mess. The story is obvious and well-treaded, with no surprises nor shocks to justify it’s extended run time. The film seems to be desperately grasping for importance instead of layering it in it’s subtext. It’s a deeply literal film, bloodless in it’s imagination and toothless in it’s social commentary. With the characters being ultra rich and out-of-touch even before the end of times, there was plenty of room for both humor and class struggles to play into the themes. But the film chooses instead to be a dragged out family drama, with eye-rolling reveals and dull, lifeless character choices.

A dour disappointment, I still find myself wanting to rewatch the film, to hope that there’s something more here. The songs seemed unnecessary and unable to convey anything that the regular scenes didn’t already. The salt mine set design does provide some eerie shots, but the bunker itself is again an unimaginative and bland setting. This is a film that is torn down by it’s own lofty goals, and my lofty expectations. Possibly the biggest disappointment of the festival.

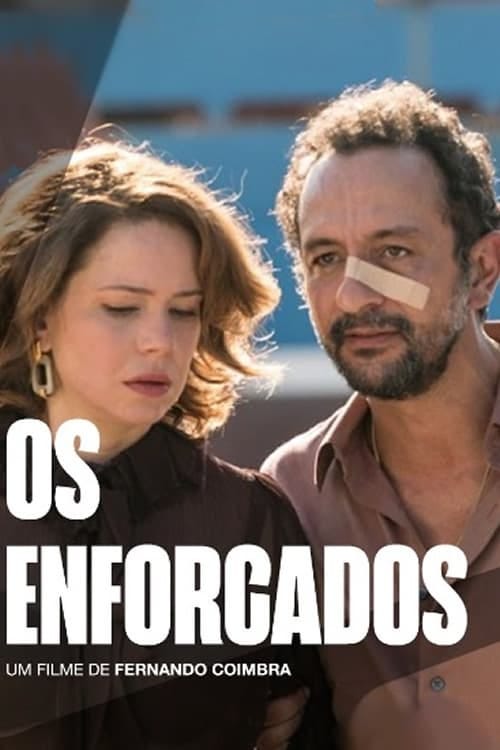

Carnival is Over

Director Fernando Coimbra

123 mins

A Shakespearean gangster film set in the underworld of Brazil, Carnival is Over does appear to be a well done, if somewhat generic, crime thriller upon initial viewing. But it’s the perspective the film takes, and the hero it decides on, that makes this film stand out from the other gangster films of it’s ilk. Following Valerio (Pepe Rapazote), the son of a gangster who was murdered the year prior, as he attempts to exit the family business. He is convinced by his wife Regina (Leandra Leal) into a heinous act that they believe will finally free them of the family burden, only to have it pull them deeper and deeper into the inky darkness of blood and cruelty. Violent and tense, the film will have you guessing until the closing moments.

While we’ve seen the story of a son turning to the criminal world of his father in an attempt to reclaim his family’s stature, Carnival is Over imbues that story with a guilt and fear that is rarely seen. The film shifts it’s focus between the married couple, one of whom is embracing the darkness of the underworld with vigor while the other grows terrified of the person they married. The chemistry between Rapazote and Leal is palpable, and every seen could end in blood or sex equally. Rapazote’s descent into madness is powerful without being unbelievable, and Leal’s fear for her life quickly becomes the most interesting part of the film.

The film leans heavily on the themes of guilt, with Regina playing the role of a modern Lady MacBeth. Constantly aware of the evidence of their evil act, she smells corpses and sees blood stains where nothing else exists, haunted by her actions. The film’s use of violence is incredibly graphic and visceral, not shying away from the amount of blood needed to be spilt for the dreams of our leads to come true. But it then takes the time to show the aftermath of this violence, the scrubbing, the cleaning, the grueling task of disposing of bodies, highlighting that violence is not momentary, but lingers, stains, embeds itself in the soil. It’s these stains and memories of violence that cause Regina to spiral into paranoia, which in turn causes Valerio to develop his own paranoia. The cycle of violence threatens to repeat itself with them throughout the film, as we grew untrusting of their actions as well.

With this violence and gore, the film does not take itself too seriously either. In fact, it openly mocks the empty lifestyle and boring lives of our bloodthirsty protagonists. These are not interesting people or people of good taste. They are tacky, dull, unimportant, and director Fernando Coimbra does not want these people to be role models. Nothing they do looks cool, nothing they do is impressive. The most disturbing scene of the film, a revenge sequence, is stomach churning instead of fist-pumping, and leaves the audience with a pit in their stomach. This is the anti-Godfather, the film that’s invested in the dangers of this world and, specifically, the gender dynamics of the criminal underworld. A fascinating and wonderful thriller.