Now that VIFF has finally ended I can return to (somewhat) regular scheduled programming. A few weeks late but there’s still plenty to discuss for September 2024 at the movies…

12 Angry Men

A towering great in the world of American cinema, 12 Angry Men is a film about the moral imperative to do the right thing. Taking place almost entirely in a jury room as twelve men from differing backgrounds debate the innocence of a young man. When a guilty verdict is all but certain to send the man to his death, one jury member stands against the rest, asking them to consider and reconsider every aspect of the case before handing down a death sentence. While initially faced with criticism and condescending retorts, he passionately makes his case, not for innocence, but for the possibility of innocence.

The film is one that shows how staging of a camera and of characters can effectively help tell the story as much as dialogue and actions. In his directorial debut Sydney Lumet shows his knowledge and control of the frame is already masterful, with a standout scene including the abandonment of a man at the table by everyone else as he goes on a racist tirade, with every man slowly but firmly getting up and turning their back on the man, his words falling on more and more deaf ears. The performances all around are fantastic, a showcase of mid-century character actors, with Henry Fonda providing a careful and incredibly convincing pillar of morality at the center of it all. A thought provoking and engaging film even over six decades after.

L’Argent

My first film from French master Robert Bresson, L’Argent may have been has last work but it doesn’t lack any of the subtle study of the human condition he displayed in his early work. Following the domino effect of a spoiled teenager passing off a fake hundred pound bill, this one act of deceit leads to lies, prison, murder, and more. Showing the cascading downward spiral of this single act, Bresson draws together everyone, not just in his story, but in the world. One can not cheat without someone being cheated, one can not hurt without someone being harmed. L’Argent highlights that all of our actions have consequences, seen or unseen, and even more directly condemns the pursuit of money as an evil act that almost only has dire consequences.

While it shows a domino effect of cascading poor decisions, the film makes sure to emphasize that it is not fate that guides the story but choice. At every twist and turn of the story, someone could make the right choice, could correct the course of our characters, and every one fails at this. It is a condemnation of the ills of greed, and every form greed can take form as. Whether it’s lust for money, time, body, or soul, it is this greed that leads to the downfall of our characters. By the time someone does show a kindness (a poor farm wife), the harm is been perpetrated, the die has been cast, and it’s here that fate has been sealed. If those in power choose to never exercise kindness, their bitterness is doomed to bleed down to everyone else. A spiteful, angry film, and an excellent end to an excellent career.

The Debt Collector

A mid-2000’s Polish drama/thriller, The Debt Collector follows Lucjan Bohme (Andrzej Chyra) as an over-zealous tax collector. We’re introduced to Lucjan as he storms into a rundown but function hospital and attempts to take a vital piece of equipment due to unpaid taxes. This is just one of many questionable and ruthless collections Lucjan goes for in the city, happily becoming the enemy of the people of his hometown. As he continues to take from those who already have next to nothing, Lucjan will be forced to question his stance when a chance encounter with an ex-girlfriend makes him reconsider his actions.

A bitter black comedy, the film unfortunately is never able to muster anything unique or unexpected from it’s premise. From the opening moments of the film we know how this story is going to play out, and director Feliks Falk strays from that predictable narrative. The film also feels incredibly dated, with the techniques popular in independent and word cinema in the mid-2000’s feeling strained and uninspired instead of adding anything thematically. It’s furtive and hyper-active camera movement recall skater videos of the time more than anything else, and it comes across amateurish despite Falk’s decades in the industry. Ultimately, The Debt Collector is a fine if forgettable post-Iron Curtain social screed.

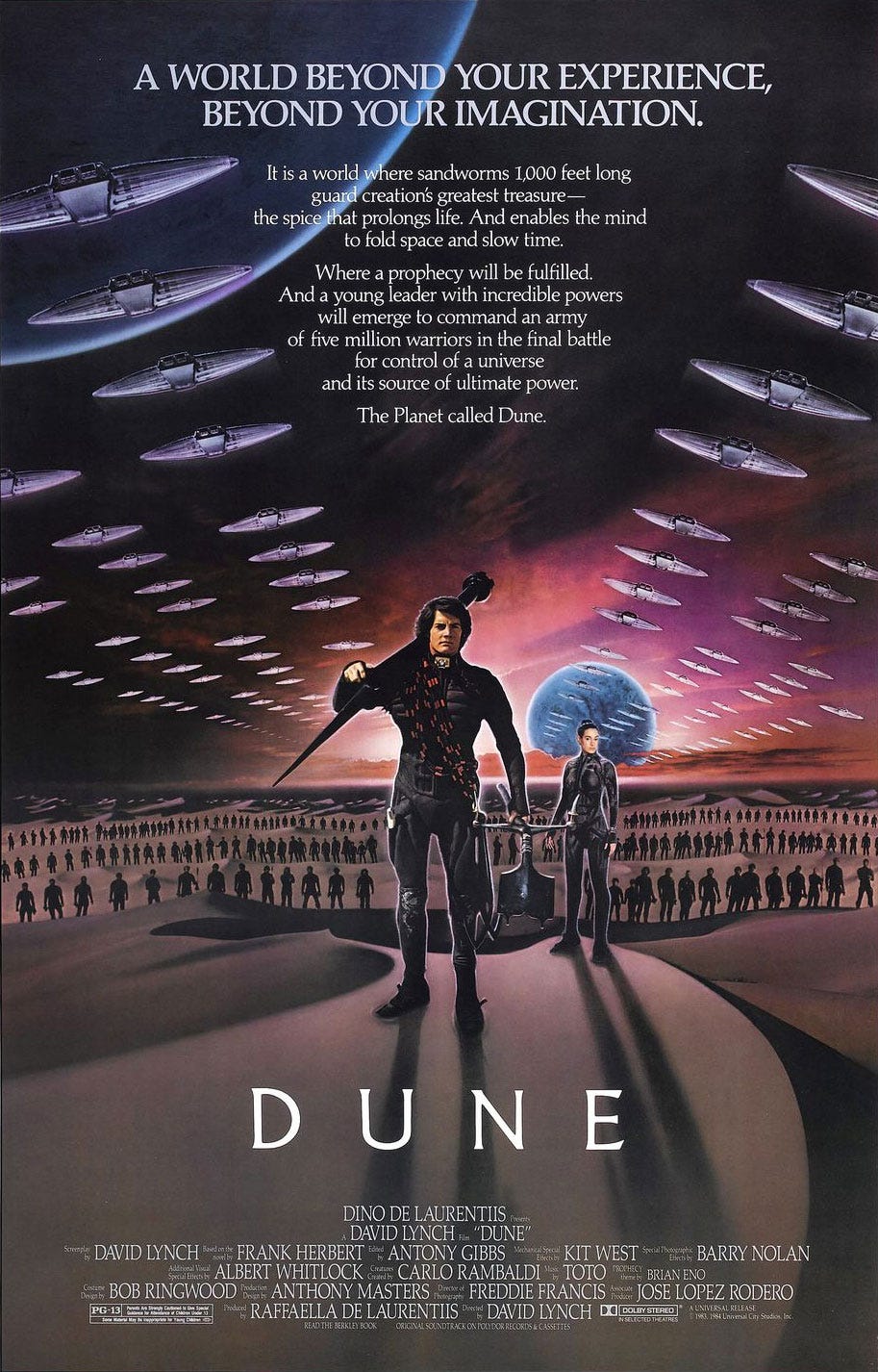

Dune

The original adaptation of the sci-fi classic, 1984’s Dune is a testament to the power of a director. Following the now familiar tale of Paul Atredias as his family is scorned by their enemies, only to force him to rise as the savior of the strange desert folk the Fremen, this film has many of the same failings as the novel. The film takes it’s time to set up our characters and the world they live in, but quickly rushes it’s final segments. We go from experiencing intimate moments between Paul and his parents to skipping years in a single cut as he rises to the level of messiah. Add to this that the ending of the film is completely different than that of the book, and makes little to no sense as to what was previously established, and you would think I would not be recommending this film.

That would be the case if not for just the right amount of genuine weirdness that director David Lynch brings to this film. The set design is perfect, a dripping grotesquery of retro-futurism. The performances, especially those of the villainous Harkonnen, are delicious in their maniacal overtures. Smaller moments of pure Lynch insanity, such as a character being forced to constantly pet a cat (who of course has a rat taped to them) in order to stave off poisoning, this is an absolutely ludicrous film. While it is not a good adaptation, the film is a truly great time for anyone wishing to scratch a bizarre itch.

EO

Exploring the world through the trials and tribulations of the titular donkey, EO is a film grasping for hope in a hopeless world. There is an almost endless cascade of misery that is cast at our animal protagonist, and through director Jerzy Skolimowski’s audacious framing we ourselves cast a deep well of emotion onto the melancholy eyes of the creature. Eo is abandoned by the owner who loves him, traded and traded and traded, sold to be turned into meat, escapes, is beaten to near death, all with his glassy, impenetrable eyes staring back at the world that has done him only harm. He is a mirror unto which we see the horrors that we perpetrate against all creatures of this world.

The film is stylistically vivid, with many sequences of wild, rushing cameras through untamed wilderness. Eo is consistently framed not just as an animal but as a central figure, a character for which we are meant to love and hold dear. So when such terrors befall the donkey we can’t help but want to look away. While narratively the film is somewhat repetitious, it is one that hopes to impress upon the audience it’s thematic weight more than to take us on an A to B journey. At times heart-wrenching, at times frustrating, it’s a film that must be seen to be believed.

Kill Theory

An uninspired, trope filled slasher that I can’t help but have a soft spot in my heart for, Kill Theory is not a film you’ll ever find on a list of the greats. Following a group of college friends as they are told they must kill each other until there is only one survivor or they will all die, the film is a college sophomore’s idea of deep. It’s particularly poorly done or slapdash, which is actually unfortunate because films where the seams show tend to have a certain life to them. Kill Theory is well made enough to be a professional film, but not well enough to be a good film, instead existing in this bland middle ground of the unexceptional. There are ideas of a good film here, but not enough talent or vision to pull it off.

That said I must commend the final moments of the film, for here there is at least a slight twist that, even now having watched it numerous times since it captured me as a 12 year old horror fan, still catches me off guard. It’s feint praise but praise nonetheless. There are some interesting kills here, and while the characters are cardboard thin there are moments of fun between certain members of the cast. Ultimately this is a deeply forgettable film that, had I not watched it when I did, would never have sunk it’s claws as far into me as I’ve allowed it to.

Record of a Tenement Gentleman

Director Yasuijiro Ozu is something of a magician on screen. Man if not all of his feels are incredibly empathetic, but never do they stumble into sentimentality. With his post-war comedic drama Record of a Tenement Gentleman this avoidance of sentimentality is almost astonishing. Following a young boy as he is reluctantly cared for by a poor vendor, the film follows as the child silently and resiliently ingratiates himself to the older woman. Over a matter of days she goes from utterly refusing to let the boy stay under her roof to having their picture taken together, a costly privilege for the time. While this could easily fall into schmaltz, Ozu deftly avoids this pitfall by showing that kindness is a basic reality within people.

Through Ozu’s lens we are reminded that gentleness and generosity are naturally occurring elements within humanity. We must give, we must love, we must accept. In a time when people are at their most defeated and still trying to put the pieces of their lives back together following the war, even then they can not turn down a child in need. As is the case in many films like this, a child in need ends of helping more than getting helped. Record of a Tenement Gentleman will not surprise you with narrative curveballs, and while the ending is expected, it is no less impactful. Here it is the journey of our characters that is the important part, not the destination. A simple, quietly passionate film.

The Sixth Sense

When discussing the early career of M. Night Shyamalan, one might be surprised by the expectations of the young director after his hit The Sixth Sense. Many touted him as the next Steven Spielberg after the release of his spectacle ghost story with an even more spectacular twist. And while these expectations have, for most, remained unmet, this film still stands tall a quarter century later. Following Dr. Malcolm Crowe (Bruce Willis), a child psychologist who, a year after a traumatic attack, is set to help a young boy Cole (Haley Joel Osment) who has a terrifying secret; he can see dead people. Hoping to help Cole process this horrible gift, Malcolm will discover things about himself along the way.

A deeply emotional story that isn’t afraid to give some truly inventive and affecting scares, it’s not without it’s trademark Shyamalan clunkiness. While his stilted dialogue and unusual turns-of-phrase would become more prominent later in his career, they still existed here. Luckily, though, it adds to the charm of star Osment, who is undeniable in his role. Wide eyed and empathetic to an astonishing degree, the final scene between Cole and his desperate, loving single mother (Toni Collette) is one of the best scenes between any mother and son put in screen. This is to say nothing of Willis, who gives one of his best performances as a quiet but assured mentor figure, willing and wanting to help this young boy. A truly loving and nerve-wracking picture all these years later.

The Third Man

A classic noir about crime and confusion in post-war Vienna, The Third Man is a highly stylish and steward of the genre. Following a pulp novelist as he travels to the city looking for an old friend, only to discovery he died under mysterious circumstances only days earlier. The film has everything one can expect from a noir at the height of the genres power and popularity; a morally ambiguous protagonist, a femme fatal who’s hiding a mysterious past, a twisty story that will leave you guessing for much of it’s run time, murder, mayhem, and betrayal. Director Carol Reed (who’s other noir Odd Man Out is another great addition to the genre) makes a masterful film of smoke and shadows.

Orson Welles is effortlessly charming and menacing in his villainous turn as an underworld crime boss, Joseph Cotten stellar as the befuddled but intrepid novelist, Alida Valli stunning and deceptive as the grieving love interest. The film is not just about the ambiguity of man, as many noirs are, but adds in the complications of language and communication. Post-war Vienna is the perfect setting, destitute and delirious, with different occupying forces having different laws and different police, the languages of man mixing in confounding and deceptive ways. What one person says could have different meanings to different tongues, and the film plays with this idea of clashing cultures in it’s subtext. A wonderful genre piece that would serve anyone good to watch.