The Favourites

The Sweet Hereafter is one of the most tragic films that I often return to. After a tragic bus accident claims the lives of many children in a rural British Columbian community, the film follows the lives of the community members before and after the accident. Tensions rise when a lawyer comes to town, making claims of money and justice, all while fighting the ghosts of his past. By tracing the quiet lives of these people and how such an unbearable sadness overwhelms everything they once were, director Atom Egoyan crafts a delicate portrait of how we continue after the worst day of our lives.

Our central figure is Mitchell Stephens (Ian Holmes), a city lawyer who comes to the community quickly after the crash. Throughout the film and Mitchell’s investigation into the crash, we flashback to a conversation he has with a young woman who knew his daughter. Through this conversation it’s revealed Mitchell’s daughter Zoe is a drug addict who has relapsed time and time again, to the point of Mitchell all but abandoning her. Mitchell’s loss of his daughter to drugs is contrasted with the loss of the children on the school bus, and the film explores the roles of parents and the role of identity in parenthood.

As you see her, two years later, I wonder if you realize something. I wonder if you understand that all of us - Dolores, me, the children who survived, the children who didn't - that we're all citizens of a different town now. A place with its own special rules and its own special laws. A town of people living in the sweet hereafter.

Parenthood takes numerous forms in the film. We see Mitchell’s stern disapproval and abandonment of Zoe, a parent turned cold to the child he once loved. We see Wanda and Hartley Otto (Arsinee Khanjian and Earl Pastko), two adoptive parents who’s deep love for their son Bear (Simon Baker) is felt in every seen with them. Risa Walker (Alberta Watson) is haunted by the death of her son Sean, as his final moments with her were spent begging not to have to go to school. Billy Ansel (Bruce Greenwood) is a single father forced to confront immense grief, being the only witness to the bus crash. Many of these people had their lives centering around their children, and in losing them their world has caved in. Those who we see exist outside of their relationship with their children are unable to maintain those lives, as the life of a parent is so encompassing that the loss of that role is one that completely destroys their sense of identity. If someone is no longer a mother or father, they can’t be anything to anybody, they can barely exist at all.

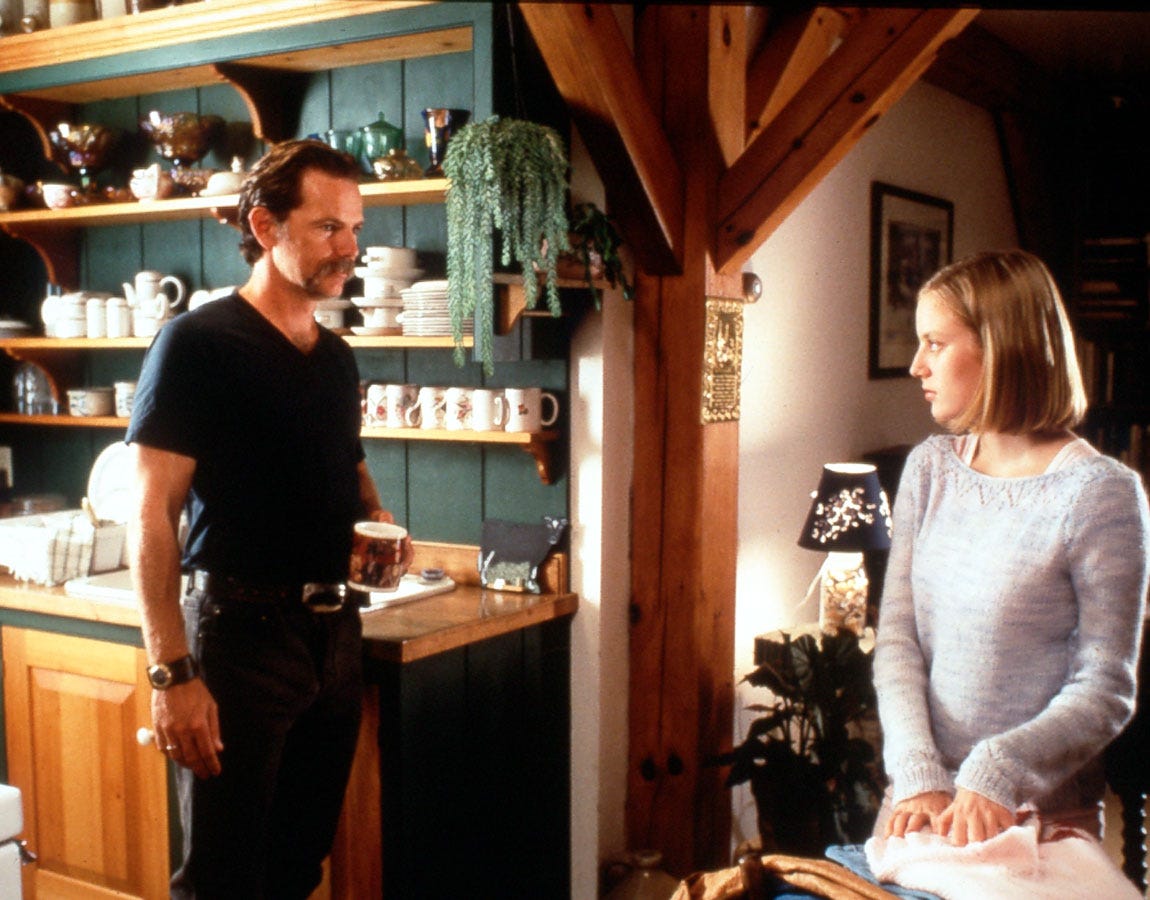

These lines of identity and parenthood are also blurred when viewing the incestuous and pedophiliac relationship between Nicole Burnell (Sarah Polley) and her father Sam (Tom McCamus). Sam has already destroyed the line that separates father and lover, so Nicole’s idea of the role of a parent is already skewed. When she returns to home in her wheelchair, discovering her father playing the role of guardian and caregiver, she’s unable to see this as truthful. Her father had already turned his back on this type of relationship, and the damage has been done. His attempts to revert to a caring father are cloying and desperate, and Nicole is able to see right through them. This is ultimately what leads her to lie during her testimony, causing the entire lawsuit to be thrown out. Nicole is able to see that the damage is done, and that there’s nothing to be gained by shifting blames.

The design and eventual fracturing of the community is beautifully and tragically captured in the film. Sam Bend is a quiet Canadian any-town, simultaneously specific in it’s quiet prosperity and its Anywhere, USA (or, in this case, Anywhere, Canada) charms. Egoyan captures the pre-accident town in a soft glory, as gentle and quiet as the freshly fallen snow. He luxuriates and long takes and giving our characters room in the frame, utilizing the close-up only after the suffocating loss that comes. We see actually very little of the town, the homes and businesses we visit isolated little oases the cold country. The community is not built from proximity but from relationships, and the cozy, lived in buildings tell us the love the walls have experienced.

The casual relations between our characters adds to wholeness of Sam Bend. While we can see the bitterness that can infiltrate a small town in the character of Wendell Walker (Maury Chaykin), we also see the neighborly love that is easily blossomed in a tight-knit community. While Wendel shows to have a memory of every transgression a community member may have committed (from drinking too much to owing money to the bank), we see that before the crash everyone had nothing but smiles and praise. A casual niceness between parents and the bus driver, parents and each other, and secret lovers, an ease of existence devoid of anxiety or pressures. Egoyan’s script easily sketches out an entire community using small smiles and glances.

But this is not some utopic paradise and Egoyan doesn’t wish to show it as one. The molestation of Nicole is the darkest undercurrent of the film, showing that there was tragedy lurking within the community already. And while not nearly as dark, the affair between Risa Walker and Billy Ansel shows that there are tensions even within the smallest and most caring of communities. Risa and Billy go on to show us the divide that forms in the town between those pursuing the lawsuit and those who do not. Billy, having already lived through the trauma of losing his wife to cancer, turns from the grizzled but gentle lover to a hard and harsh man following the death of his children. Risa, on the other hand, has all but broken down completely, her final conversation with her son haunting her as she’s the one who convinced him to go to school that day. She trembles and weeps constantly, shaken to her core and vulnerable to the belief that anyone but her is responsible. She’s the perfect person for the influence of Mitchell Stephens.

We see both of these temperaments within Stephens treatment of his daughter; he was the loving, weeping, trembling man who would do anything for her, and he is now the hard, untrusting man who has been damned one too many times. Stephens tells the story of how, when his daughter was young, she was bit by a brown recluse spider, and had they not made it to the emergency room in time he would have had to perform a tracheotomy on her. He emphasizes how, in that moment, he was willing to do anything for his daughter, including a terrifying act of violent medical intervention. We compare that to his treatment of his daughter now, the disdain in his voice when she calls and the pain in his face discovering she’s tested positive for AIDS. Stephens believed he had lost his daughter long ago, that the girl he would do anything for was long washed away in a sea of drugs and destitution. He had thought he did all he could and that that was not enough. In the moment he finds out about her diagnosis, though, we see that he had a glimmer of hope for her, a fraction of redemption he had held onto, that he now knew was never going to come to pass.

I didn't have to go as far as I was prepared to. But I was prepared to go all the way.

Stephens loss of Zoe informs his desire to pursue the lawsuit. Stephens sees both himself and his daughter as failures, him for his inability to keep his daughter protected, and Zoe for her inability to keep herself clean. While he is an ambulance chaser, and it is never fully clear if he believes in the lawsuit, it does appear that he wishes to relieve the guilt from the parents and from the bus driver Dolores Driscoll (Gabrielle Rose). He needs to believer that there was something that was missed, something that can take the weight of guilt off the parents who simply sent their children to school that morning, for if there is something to relieve their guilt, the same could be true for him. This is not a case to prove that their was a failure, but to prove there wasn’t, to prove that someone else can share this burden.

Billy Ansel is able to see that there is no guilt to be found here, that no one is to blame for anything, and that sometimes the world is just going to break you. While there is no direct dialogue in reference to God or religion, the actions of Billy are guided by a frailty in belief. After the death of his wife he devoted himself to his children, and allowed himself the temptation of Risa. But he tells her in their final rendezvous that the thing he appreciated most about their clandestine meetings was not the sex nor the company, but the nights when Risa was unable to sneak away and he would spend the entire night sitting alone. Billy is capable of taking the harsh disappointments and sitting in them, sitting in despair, and not allowing it to overwhelm him. He sees clearly that hurt has no higher meaning, that death has no purpose or design or reason. Sometimes life is sweet when your lover can sneak away, sometimes you must sit in the dark. It’s up to you to make both possibilities bearable.

These ideas of guilt and punishment are reflected in Nicole’s story of the Pied Piper that she tells to the Ansel children. Billy’s son Mason asks why the Piper would take the children instead of using his magic to make the townsfolk pay his fee. Nicole says that he wanted to hurt the townsfolk by taking their children. When the people of Sam Bend lose their children, they similarly start searching for the why, because something this terrible has to have a reason. But this isn’t a fable, and there is no moral.

The closest thing to a punishment that occurs in the film is the testimony of Nicole, who lies and derails the possibility of a financial settlement. To the townsfolk this is a seemingly random lie, something that can not be disproven but is known to not be the truth. It’s a bitter thing they can not understand but that they must accept, much like their other losses. To her father this is retribution, a punishment for his sins, a burden he will carry himself, for while Nicole may never accuse him of his molestation, she has still made him a pariah. For Mitchell this is a punishment for his schemes, his lies, his own abandonment of Zoe. He pursued a phantom cause, wishing to place blame on a failure that never happened, much like he wishes to find a cause for Zoe’s addictions. But some things are inexplicable, some things are inevitable, and there is no justice or reason to tragedies, whether personal or that of a community. Nicole’s testimony is, for him, another random act, another thing that simply went wrong for no reason at all.

Why am I telling you this, Mr. Ansell? Because we've all lost our children. They're dead to us. They're killing each other in the streets. They wander, comatose, at shopping malls. Something terrible has happened. It's taken our children away. It's too late. They're gone.

The town is left living in the sweet hereafter, the bitterness and beauty and stark pain of existence. The sweetness of life after tragedy occurs long after the tragedy, long after the dead have been buried and the tears have dried. The sweet occurs when a mother can laugh at a memory again, or a bus driver can smile while loading up her passengers. There is a resonance, an echo that will likely carry on for generations within the community. When someone passes, years from now, their obituary well mention their predeceased son or daughter, and the townsfolk will whisper condolences while hoping the parent and child have been reunited in the after. That’s the sweet hereafter, the little moments that will gather up to rebuild a life after such a loss. Every word will be formed with it, every milestone will be marked with it. A town built on a new foundation, a sadness that permeates every moment until that sadness itself is the town. Or the life.

Mitchell Stephens has lived in the hereafter the entire time we see him on screen. His harsh worldview has been completely formed by the loss of Zoe, and he exists in a perpetual state of bitter regret. The failure of the trial is the towns rejection of this bitterness, a way for the wound to scab over. Mitchell was never able to forgive himself for what has happened to his daughter, and likely never will. Sam Bend must embrace the sweetness of loss, the eventually turning of the clock, or they too will be doomed to a quarter of an existence. When we see Dolores at the end of the film, once again driving a bus, happily loading passengers, we see in her and Mitchell’s faces the choices we have; we can accept the sweetness of the hereafter, or we can let it consume us.