The Favourites

The Elephant Man

When discussing the films of David Lynch, heartfelt is rarely a word that comes up. The American auteur has become known for his surrealist delves into the human condition (so much so that his own name has become a shorthand within film criticism) but in matters of the heart he is not often regarded. I feel this is an unfair treatment, as within his film The Elephant Man we see that Lynch handles carefully the ideas of love, adoration, loneliness, and belonging, and the powers these emotions can hold over us. While the film is a much more straightforward narrative than many of his other works, the care with which this narrative unfolds puts this film up there with his other masterworks.

Heavily inspired by other works, most notably the classic Universal monster movies of the 1930s and 40s, Lynch tells the true story of John Merrick, a man cursed with a tremendously hideous form. Everything in life is difficult for Merrick, “The Elephant Man”, due to his deformities, from eating to speaking to breathing. But most notably it’s his ability to form connections that his form has robbed from him, at first because of the rejection from others and then because that rejection has made John a cautious man. Even when presented with a kind hand, Merrick refuses it at first, for everything given to him until that point was pain and harm. This is a story of accepting the kindness of others in a world so cruel.

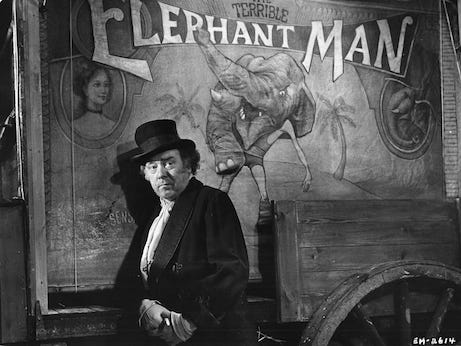

The film is presented in its first half as a classic monster movie, one made to frighten teenagers at late-night drive-ins. The black and white pallet that Lynch uses is heavily covered in bright whites in deep blacks for the first half, the contrast casting suspicions upon the unknown creature we have yet to meet. For the first thirty minutes of the film, we do not see “The Elephant Man”, his image hidden from us and his name spoken in whispers. This builds tension as Doctor Frederick Treves (Anthony Hopkins) searches for the creature. Treves is presented in the way of the classic hero from these horror tropes, the highly educated Englishman who doesn’t believe in the supernatural but is keen to it nonetheless. While there is nothing supernatural in the life of John Merrick, it’s the playing of these tropes that heighten the reality of the film.

The single tear Treves sheds when first looking upon John is when the film turns away from the more horrific aspects of the Universal tropes. While films such as Creature From the Black Lagoon and Frankenstein do hold sympathy for their creatures, never would they pity them as Treves initially does Merrick. This is a monster of the real world, something horrific to see, true, but it’s not a threat, and it’s nothing to fear. In that moment we discover that the monster is indeed a man and that this man has had a terrible cruelty placed upon him.

The audience is conditioned to think that John will be a monster, as the others briefly seen within the “freaks” section of the carnival are portrayed as gaudy and maniacal. We are placed in the position of the gawker, the spectators who think not of the humanity in these creatures but of the bizarrity of their form. This plays later in the film as will, as it is his fellow sideshow performers who show John the freedom he deserves. Though not a Universal monster movie, Tod Brownings Freaks is heavily inspiring here, with Lynch showing more humanity in these outcasts than in the majority of “normal” society.

This lack of empathy is what causes John to be initially uncooperative with Treves in the hospital. He sees Treves is another master, another person ready to make him a spectacle. John’s life under the uncaring thumb of Bytes has ingrained in him a belief that he is not a man. Day after day he was trotted out in front of horrified spectators, not one of whom ever tried to help him. The presentation Bytes gives before revealing Merrick reinforced the idea that he was indeed the “Elephant Man”, neither man nor beast, but a horrific combination of the two. Only through the kindness of Treves is Merrick able to start separating himself and the Elephant Man persona.

The Bible passage used to start that separation is of importance. Specifically, Psalm 23 states “Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.” On this line, the two doctors realize that John is reciting the passage from memory, not simply parroting the lines Treves had fed to him earlier. The passage speaks about acceptance of one’s life, of fearing not the pains within it but celebrating the joys that can be found in it. Through this celebration of the little joys, one can expect to be accepted into the graciousness of the Lord. While not a religious text, within the world of Lynch, it’s the acceptance and giving of kindness that eventually frees John Merrick from his burden of loneliness and desperation. The passage ends “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.” This mirrors the ultimate fate of Merrick, who takes the mercy granted to him by his newfound friends and lives his final moments with the grace of their kindness. Here the Lord is not God, but simply the company of the kind.

Never. Oh, never. Nothing will die. The stream flows, the wind blows, the cloud fleets, the heart beats. Nothing will die.

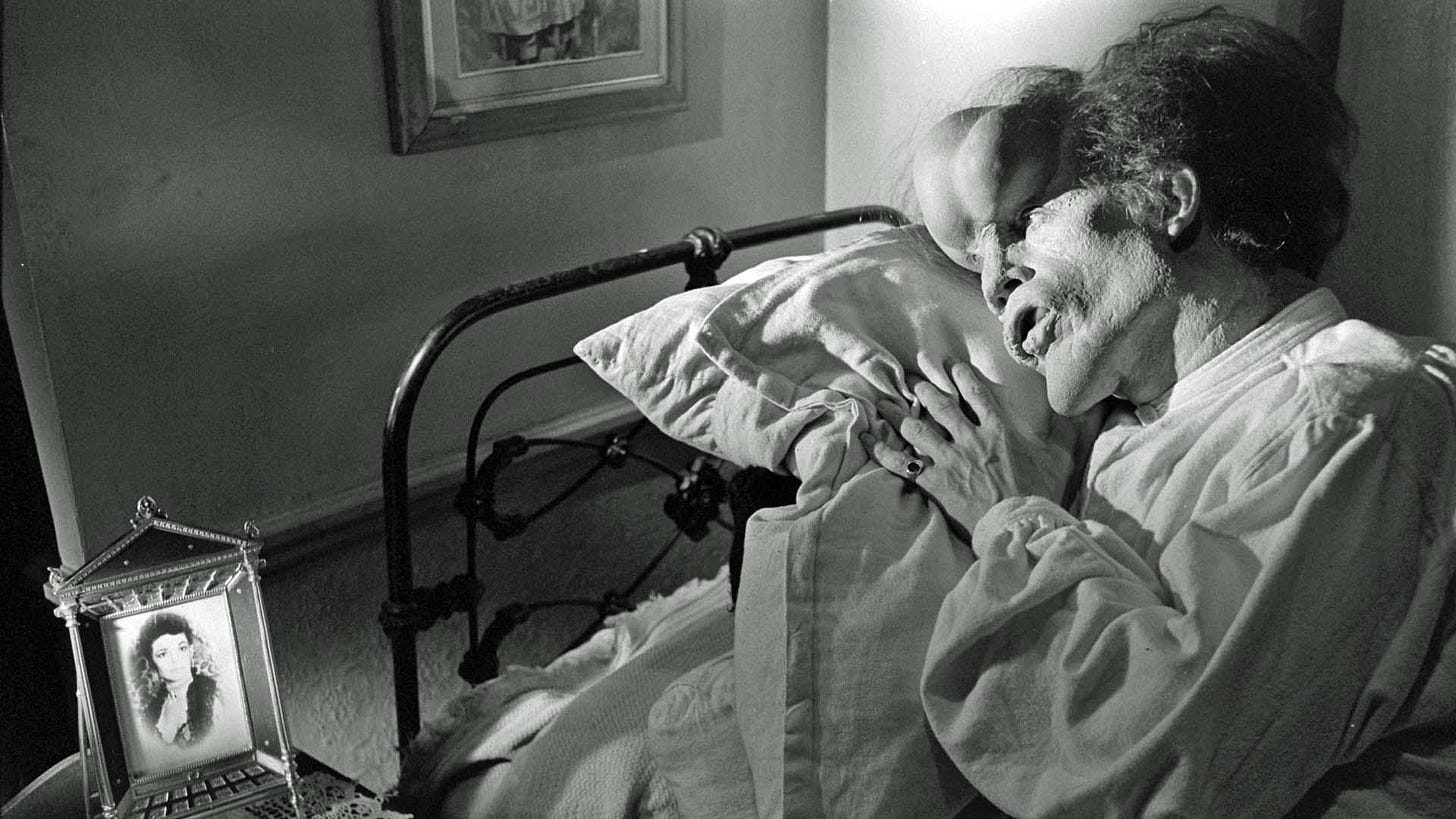

This is also mirrored in these final lines of the film, echoed memories of words once spoken by John’s mother. John, having finally fully expelled the “Elephant Man” persona, chooses to sleep like a proper man. Even though he knew this act would likely kill him, he feared not, for nothing ever dies. He knew that his effect on the hearts of the people around him had changed them forever, as they had changed him. And as long as those hearts exist, and the hearts they touched, and so on and so forth, nothing dies. Love is the stream that flows, the wind that blows. It is the unstoppable, natural force that affects us all, and is what will make us live forever.

The separation of John Merrick and The Elephant Man is a long process in the film, one that Treves doesn’t even realize he is hindering at first. It takes the head nurse, Mothershead, to point out to him he has become the master Merrick so feared, just one who gave the carrot instead of the stick. The socialites who came to see Merrick were no different than the spectators of the sideshow, conversing with John but not respecting him as a man. They continue to be amazed by his eloquence and his humanity, as they still see only the monster. It’s only through the proper treatment of some of the people around him, including the nurses and eventually Treves, that Merrick is able to surpass his ailment and fully become the man he is.

During the time he is sitting with these socialites, he is still having nightly visits from gawkers paying the night porter Jim. His new home continues to be the cage that he had always known. This allows Bytes to kidnap him, only to discover he has changed. Merrick at this point has seen the light and no longer performs as a freak show, for he is not a freak show, but a man. Abandoned by Bytes as worthless, Merrick makes his declaration upon returning to London. Chased down at the subway station, people once again reverting to a mob of slack-jawed watchers, Merrick cries out his now infamous line, declaring the death of “The Elephant Man” in the process.

I am not an elephant! I am not an animal! I am a human being! I am a man!

John Merrick has emerged victorious in the battle for his mind and body.

The opening and closing of the film are symbolic of this fight between myth and reality that rages inside Merrick. The dream-like sequence that tells of how Merrick was inflicted with his condition overlays elephants and his mother in a hallucinating nightmare, and we fall into a near trance as the film blurs the lines between man, animal, dream, and reality. Merrick’s life begins as this nightmare, an inability to separate his two personas. By opening with this myth Lynch builds the idea that there is something mystical, something otherworldly about Merrick, a man who is simply sick.

In closing in a surrealist exploration of death, Lynch embeds his death with this myth as well. We are left to question whether this death was suicide, accident, or acceptance. In death, Merrick is also transcribed into history, “The Elephant Man” entering myth while Merrick enters death. Death is the final separation of Merrick and the Elephant Man, one is destined to dust and the other is destined to history books. In these dream moments explored by Lynch, he recognizes that, after death, the stories told about us are not who we were, never fully at least, and it’s at that moment our being becomes lore instead of soul.

The main cry that The Elephant Man rallies for is kindness. Some may view pity as kindness, or empathy as kindness, but the film forces us to see that these are just forms of avoidance. True kindness, the kindness that can truly change a person, is hard work, is an endeavor, and something that takes time, effort, and precision. But it can change the world for the better, and that’s all that should matter.

That last paragraph is truly great. Wonderful review as always. Thanks!