The Favourites

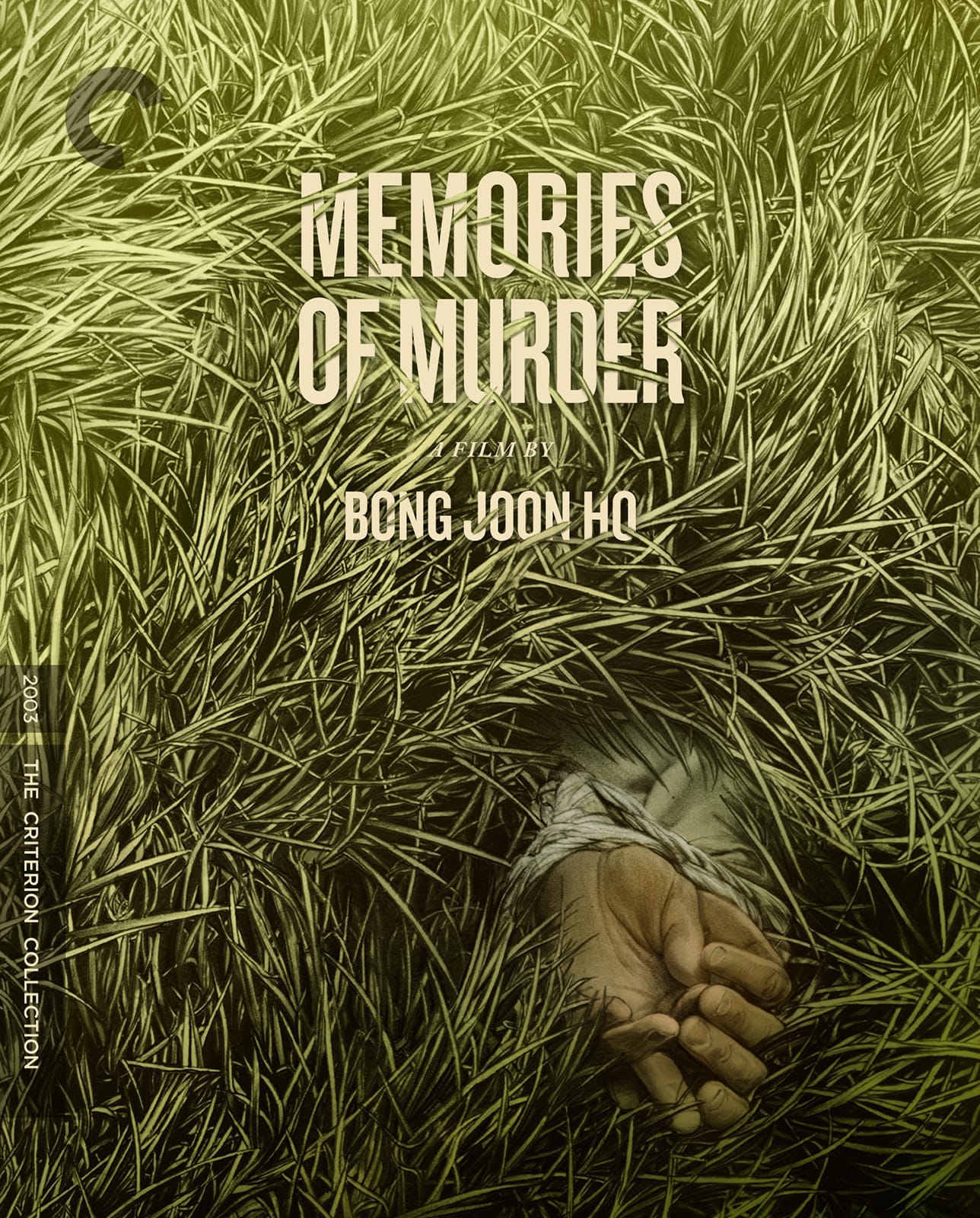

Memories of Murder

Bong Joon-ho’s 2003 masterpiece Memories of Murder follows a group of small town detectives as they become steeped in the crimes of a serial killer. Having never encountered crimes such as these, the police are completely out of their elements, and through their cockiness and false bravado they constantly let down the people in their community. The film is a condemnation of not just the evil killer, but the systematic abuse and privelages taken by those in power that allow such dangers to continue to lurk in the shadows. This is not a film where good triumphs over evil; this is a film where good is a corrupted, rotten thing. It’s only through reflecting on this corruption that the police are able to move forward in their work, but by then it’s far too late.

The four male detectives we meet represent different elements of this corruption and failure. Park Doo-man (Sang Kang-ho) represents bravado and over-confidence. His belief that he can tell a criminal just by looking in their eyes is proven wrong time and time again, but he never backs down from his claim, showing that the truth is not as important for him as his gut feeling. Seo Tae-yoon (Kim Sang-kyung) is the Seoul detective who comes to the small precinct in order to help with the investigation. While he is by far the most competent of the detectives, he still displays arrogance in his unwillingness to share ideas with the other detectives. While rightfully seeing them as buffoons, he fails to see he is unable to solve this case on his own. Cho Yong-koo (Kin Roi-ha) represents brutalism, as his only characteristic is his willingness (and near glee) in torturing suspects. Their sergeant Shin Dong-chul (Song Jae-ho) represents the corruption of bureaucracy, as he’s unwilling to discipline his staff if their torture gets the results he wants. All of these men care more about themselves and how they are perceived than with finding the serial killer that stalks their town, and the killer escapes because of their various levels of selfishness.

All of their flaws can be traced back to toxic masculinity. They are prideful to a fault, boisterous and full of false bravado. Multiple times their own insecurities stop them from listening to sound advice, such as when the lone female police officer Kwon Kwi-ok (Go Seo-hee) tells them that the same song plays on the radio every time a murder happens. The rivalry between Seo and Park causes them to miss clues and infight, giving the killer plenty of time to attack again. The torture of their suspects and forced confessions show their allegiance is not with the truth, but only with their success. Through the first half of the film these failures are played for laughs, for farce, as it would almost be hard to believe the incompetence on display otherwise.

The comedic approach of the first half of the film is what separates this from many of it’s American counterparts. There is an absurdity to serial killings, to the methodical nature of the crimes, and in the case of this film, to the complete inability of the police to handle this level of crime. When Park is investigating the first handful of crime scenes, they are filmed as po-dunk, fish-out-of-water sequences. At the first crime scene we see how little authority Park commands. Not only is he unable to stop a group of young boys from playing with underwear that’s evidence, he’s continuously mocked by a young boy who parrots everything he says in a faux serious manner. At the second crime scene Park tries again to play an authority, attempting to cordon off a footprint and stop onlookers from destroying the scene, and yet again he fails in terrific fashion. And while his failure ultimately is at the cost of the lives lost, by playing it for laughs director Bong is able to turn his lead character into a buffoon. Bong knows he is not someone who has earned our respect yet, police badge be damned.

These comedic beats also play out throughout the interrogation and torture scenes. Probably the funniest reoccurring bit in the film is Cho constantly dropkicking suspects on a moments notice. Despite being unequivocally police brutality, the dropkicking evokes the work of Jackie Chan in it’s comedic beats. The interrogation scenes are crafted as slapstick, as farce. The frustration the police show when their coerced confessions inevitably fall apart are hilarious in how pathetic they come across. Played more like a frat boy comedy where the nerds say the wrong thing instead of the serial killer drama they should be, Director Bong uses our expectations for what a serial killer film is to create these comedic moments, further proving the police to be the fools.

Even as the murders continue and the investigation should be more serious, the immaturity of Park forces the film to continue it’s comedic path. Park is a deeply flawed character, a boastful, prideful idiot. One of the funnier moments of the film includes his false confidence in identifying the man who was masturbating at the crime scene. Even though he uses proper detective work in finding the man (by spotting the women’s underwear he’s wearing) he makes Seo believe he found the suspect through his ability to find a guilty man by looking in his eyes. When Seo believes this gift, the camera does a slow dolly in on Park proudly and triumphantly drinking from a stolen flask, taking the stance of a victor even when the audience knows the lie he has put forth. His pride is his downfall here, as it is in the public baths scene, where he spends a night looking for a hairless man. He even states that the staff laughed in his face, showing that he has fully taken on the mantle of the fool not just to the audience but to the public within the film.

Chief, I may know nothing else, but my eyes can read people. That's how I survive as a detective, and why people say I have shaman's eyes.

The comedy of the film collides in dramatic fashion with the horror of the film near the halfway mark. The police, completely incompetent and dysfunctional, begin to come apart at the seams. Park and Seo have yet to agree on any aspect of the case, the torture of their suspects is becoming worse and the public has turned against their efforts completely. It’s on one specific night when Park and Seo get into a physical confrontation around the time that another murder takes place that the detectives begin to see just how their inabilities have failed their community. It’s after this murder that both Park and Seo can see how they’ve been going about the investigation in a selfish manner, and here that Director Bong changes the tone of the film from a comedic skewering of police misconduct to a remorseful examination of personal and government failure.

While our characters take on a more serious pursuit in the second half of the film (including having Cho placed on administrative leave due to his unwillingness to stop beating suspects) we see that these efforts are too little, too late. In the first half of the film, important evidence is misplaced and destroyed in comedic fashion, while in the second half we see the repercussions to this carelessness. They have no real leads. They have no real suspects. And they don’t have the faith of the public. The hardest defeat they face at this point is the realization that not only are the starting with almost less information than they had before, but their only hope to move forward is to wait for another murder to happen. They’re immaturity has made them completely helpless.

This helplessness eventually curdles into rage and frustration as the killer continues to escape their clutches. When a new suspect emerges, his calm demeanor and unshakable answers cause Seo to become more erratic. He is fully convinced of the man’s guilt, but unwilling to resort to the previous torture, there is nothing he can do. When another murder happens on a night he was planning on tailing the suspect, he breaks completely, handcuffing and beating the suspect. Moments away from shooting him, the suspect is saved by Park when he reveals the DNA evidence had returned from America and it did not match. Seo, unwilling to accept this, still almost kills the suspect. He has been broken down from the stoic, hardworking detective he presented himself as. His toxicity has finally manifested itself, and in that moment he proves he was not more capable than the local police.

We see it’s through the general dismissal of women that the police continue to fail the public. This is most obviously seen with the treatment of the only female officer, Officer Kwon. When she presents her discovery of the same song playing on the radio on the nights of the murder, Park dismisses her outright. When this lead proves to be fruitful, Kwon is not given the credit she rightly deserves. Upon discovering a survivor of the killer, she refuses to speak to the male detectives, her trust only residing in Kwon. By this point the men have proven they are not to be trusted, and the women must watch out for each other.

The final victim is what brings all the failures of the police into complete focus. A young girl that Seo had encountered at various points throughout his time in the small community is the final victim. Having the victim have a personal connection with the police is another representation of the disregard of women, implying that the horrors these women have faced only come into fruition for the detectives when it has affected them personally. This is a common reality women face, as they are disregarded when they are victims, and justice is only sought when it affects those within the patriarchy. The implication of this final death is that the detectives see it as innocence lost, when they should have seen every victim with such regard and tenderness.

The film ends by jumping forward to present day 2003. Park is now a salesman, having long left the police after this case went cold. On his way to a job he stops to visit the scene where the first body was discovered. A little girl tells him a different man had done the same recently, saying he had done something there a long time ago. Asking for more specifics, the girl tells Park that he was just an ordinary man. In the final moments, Park turns and faces the camera, staring down the audience, the accusation firm and condemning; the killer is out there, among us, and justice will one day be served. It’s in these final moments we see Park robbed of the bravado of his position, broken down and haunted by the horrors he was never able to solve. Stripped down to a bare man, now he does have the power he claimed he had before. Now he can see the guilty sitting amongst the audience.

This final act of condemnation was explicitly put in the film by director Bong for the perpetrator of the real life crime (as he’s stated he believed the killer would watch his film), but the searing contempt held within that shot does bleed over to the audience. An audience that laughed along to buffoonish torture and failures, an audience that consumes the content of murders for entertainment. We never hear the names of the women attacked, nor visit their families, or see the holes left in the lives of those they left behind. In this closing frame director Bong asks the audience if we are complicit in the failures, and in the systems that allow men like Park to maintain power. Can we condemn these men without acting ourselves? Park looks at us, as we are as guilty as he is in the failures of the modern world.